Voyagez Plongez Shootez

Le plaisir de partager mes voyages et mes images

Des expériences et des rencontres inoubliables

Je suis Yves Guénot, après une carrière à l’éducation nationale et au Ministère des sports , je suis à la retraite et profite du temps qui m’est donné pour satisfaire mes passions : voyager, plonger et faire des images que je partage volontiers avec tous mes amis . Montrer différents coins de notre planète et leurs beautés me laisse croire que chacun prendra conscience de l’importance de respecter et protéger cet environnement fragile qui nous accueille . Je mesure la chance qui m’est donnée de pouvoir visiter et admirer ces endroits merveilleux que j’essaie de vous présenter …Ce n’est que ma vision, elle se veut modeste , j’espère qu’elle vous plaira …

N’hésitez pas à communiquer avec moi , dans le respect et la courtoisie , et même à donner des liens vers vos blogs ou images . Nous pourrons ainsi échanger des adresses, conseils, astuces …pour et autour de nos voyages ou passions …Mes images ne sont pas libres de droits , merci de respecter mon travail …Peut être un jour elles seront à la vente , pour amortir un peu toutes les dépenses afférentes à cette passion !!!

Merci

Promenez vous dans les menus déroulants en haut de page , n’hésitez pas à commenter et à échanger avec moi .

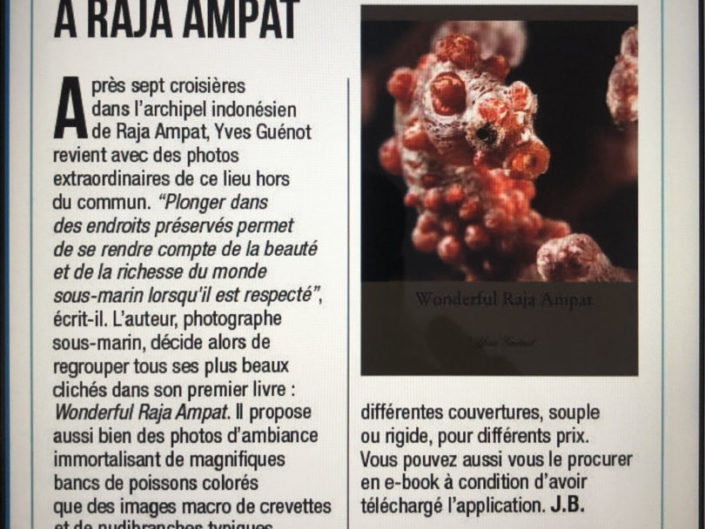

et si mon livre ou mon Ebook sur le Raja Ampat vous intéresse c’est là :